During one of the Montgomery dinners at Dartmouth, I met Viktor Witkowski, a painter and Visiting Faculty at Studio Art Department) with his partner Katie Hornstein, a Professor of Art History – introduced to me by a mutual friend, artist Anthony Viti. Both had brought family photos to share at an impromptu Digital Diaspora Family Reunion (DDFR) over dinner.

During one of the Montgomery dinners at Dartmouth, I met Viktor Witkowski, a painter and Visiting Faculty at Studio Art Department) with his partner Katie Hornstein, a Professor of Art History – introduced to me by a mutual friend, artist Anthony Viti. Both had brought family photos to share at an impromptu Digital Diaspora Family Reunion (DDFR) over dinner.

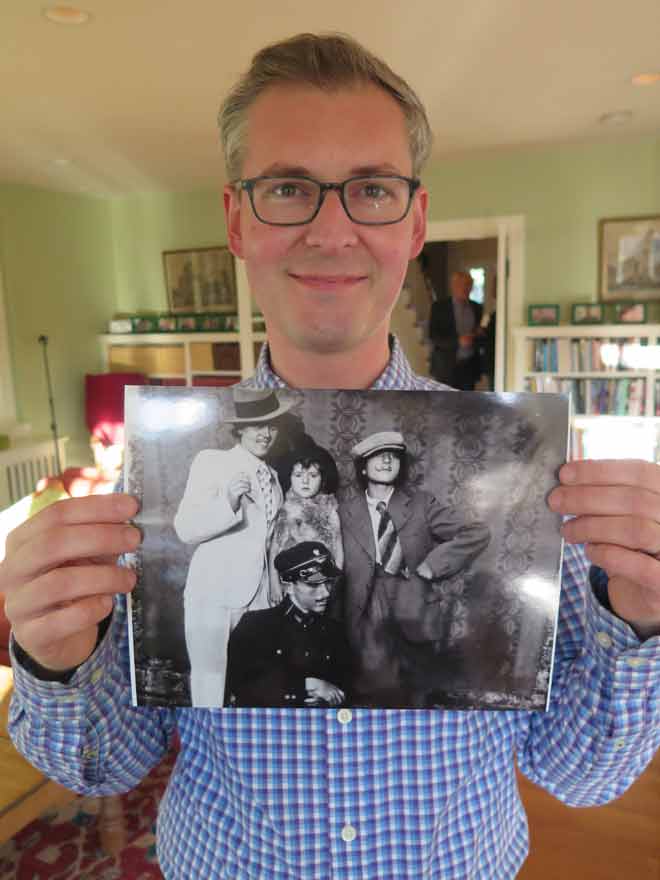

Katie had printed out a photo that Viktor had saved from burning in a fire in Poland – it was a 1930s carnival-like image – with everyone playing dress up and including Viktor’s Grandfather, his Jewish daughter born out of wedlock and Viktor’s Great Aunt – who he informed us was a Lesbian.

Soon after we met, Viktor left the New Hampshire to begin a residency in Poland. While there he visited his family and made the upsetting discovery that his father, like his great aunt, had recently burned much of the family photos in his procession. It was heart breaking for Viktor especially after participating in DDFR. Viktor and I continue to correspond and recently, he sent images of his work in Poland as well as reflections on the impact of the Syria refugee crisis in Europe as seen through the eyes of the artist.

Below is the narrative between Viktor and DDFR over the last couple of months.

Viktor Witkowski shares his unique photo and story at the DDFR roadshow in Dartmouth College.

Viktor: I’m originally from Poland. This is where this photo was from. In this photo you have my Grandfather. This photo was Probably taken during the end of the 1930s. You have my Grandfather (squatting) and my great aunt dressed in male clothing (on the left). This is my Grandfather’s first child – whose mom was Jewish and she is lost to the family and on the right is another family friend about whom we have no information.

DDFR

Viktor: What’s interesting about this photo is that I first met my great aunt when I was around 12 years old or so. We met her outside of Krakow in Poland. And it’s the first time I meet her and the first question she asks me was ‘Viktor, do you like girls?’ I thought this is a weird question to ask me. I’ve never met you. Never seen you and this is the first question you ask me. Later on my parents told me that she was queer but that no one in the family was talking about that. She had a fiancé before the war but they were never married and she lived most of her life alone. When we visited her, the day before, she started burning photos and throwing them into the fire, into the oven. And we were able to recuse two photo albums and not all had that many photographs in them. But we were able to secure some. And this is one of them. Where they played dress up. We don’t have much information on it. This is all we know

DDFR: Why did you choose to share this photo?

Viktor: The family history is really fragmented mainly because of the war. A lot of the family items got lost, a lot of the family narrative got lost, people didn’t want to talk about the family after the war based on the experiences they had. And so this was a compelling photo to bring where you have a photo but you only know a little about the people you call your family in Particularly her narrative being queer in pre WW2 Poland and living a lie afterwards. She wasn’t very happy and I really liked her but I didn’t really get to know her and she died shortly afterwards.

Watch an exclusive peek of Viktor’s Interview!

Dear friends,

Greetings from Germany!

Niedersachsenstein in Worpswede (WW1 monument made entirely from brick), screenshot from HD video

Since the start of May, I have been living and working at the artist residency “Kuenstlerhaeuser Worpswede” . To some of you Worpswede might ring a bell due to the painter Paula Modersohn-Becker and the artist/architect Bernhard Hoetger who were part of the local artist colony in the early 1900s. My current project addresses the visible and invisible challenges that have emerged across communities in Germany with the arrival of over one million displaced people from conflict zones.

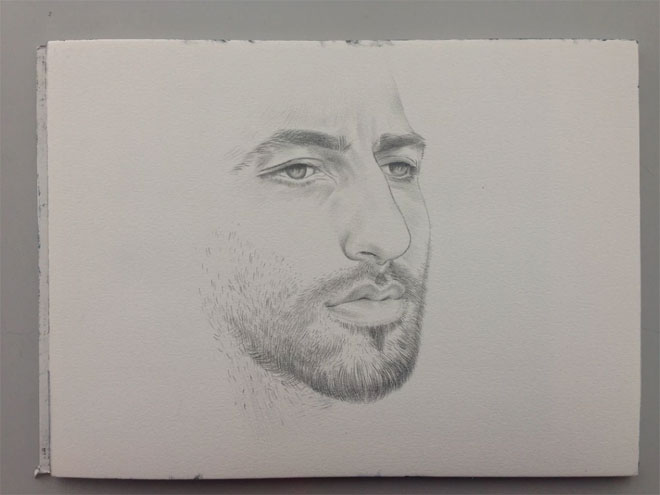

Alan, pencil on cotton paper, 9″ x 12″, 2016

In the last three weeks, I have traveled various cities and towns in northern Germany in the vicinity of Worpswede, including the city of Espelkamp where I grew up after my parents had fled Poland in the early 1980s. This is where I met Alan from Syria, pictured above. He and a group of mainly Syrian refugees have been living at my former elementary school for seven months now. While Germany took in 1,2 million refugees within the span of a year, the US has welcomed only 2,500. As a result, virtually every community in Germany is affected and strained. Because the majority of refugees has arrived within the last 7 to 8 months, it was important for me to visit Germany at this point in time, as global attention toward the ‘refugee crisis’ is already waning while the situation on the ground is far from resolved.

Container Homes for Refugees in Bremen, screenshot from HD video

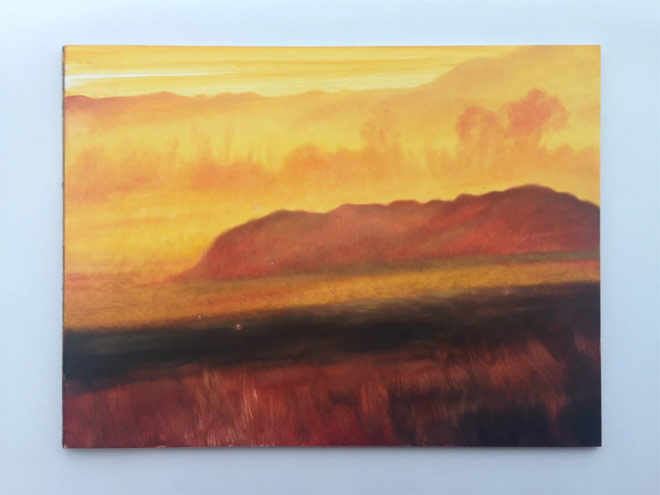

This incredibly complex, confusing and at times frustrating situation led me to work across a range of media as I found it impossible to respond to these experiences in one medium only. My encounters with people are recorded in video and photo, while I am also working in drawing and painting to explore portraiture and landscape painting. Aside from meeting and talking to various people on both ends of the ‘crisis,’ I have been visiting as many locations: understaffed offices, former parking lots that now house containers for refugees, gym halls, overcrowded living quarters, big city centers, city suburbs, rural towns and parks. I decided that in addition to addressing the human component (and the toll it takes), I must take the meaning of ‘place’ (or Ort in German) into consideration. What does it mean to leave your home and arrive at a place that is neither home nor homeland? Why are most refugee housing sites located on the outskirts of town? What effect do they have on the local community and the refugees?

Donka Dimova* in her conference room/hallway, screenshot from HD video

Any consideration of ‘place’ is not complete without addressing the concept of landscape. Firstly, based on the landscape here in Worpswede and northern Germany in general, I started thinking about the difference between heartlands and borderlands and how refugees are generally restricted to the latter. Secondly, the idea of landscapes as an externalization of inner conditions is not a particularly new one. Both sides, the volunteers and social workers who try to improve conditions and the refugees who try to build a new life for themselves are continuously slowed in their tracks by political indecision and a bureaucratic apparatus nobody knows how to change. Under these circumstances each individual’s emotional and psychological state is continuously challenged which raises the question how I can use landscape to address these deeper layers.

Worpswede Landscape, oil on paper, 9″ x 12″, 2016

For example, I met a family from Afghanistan (a married couple with three young kids) who were visiting from their overcrowded camp in Hamburg; they are here to spend a few days in this picturesque town of Worpswede, the countryside. In order to leave Hamburg, they had to apply for a permit. Once the permit was granted, they received their travel documents which are only valid within Germany. Since their arrival, they have been enjoying their time away from the refugee camp, where they do not have any privacy and where they are not even allowed to cook for themselves. On vacation here, their kids have even started to learn how to ride a bike.

Screenshot from HD video

Breathtaking life experience. Beautifully documented in every medium of art. As an artist & filmmaker, this story speaks me on so many levels. It’s inspiring me to revive a film I started in Bosnia. Thanks for sharing this. Riveting.