“Strong Island chronicles the arc of a family across history, geography and tragedy – from the racial segregation of the Jim Crow South to the promise of New York City; from the presumed safety of middle class suburbs, to the maelstrom of an unexpected, violent death. It is the story of the Ford family: Barbara Dunmore, William Ford and their three children and how their lives were shaped by the enduring shadow of race in America. In April 1992, on Long Island NY, William Jr., the Ford’s eldest child, a black 24 year-old teacher, was killed by Mark Reilly, a white 19 year-old mechanic. Although Ford was unarmed, he became the prime suspect in his own murder. A deeply intimate and meditative film, Strong Island asks what one can do when the grief of loss is entwined with historical injustice, and how one grapples with the complicity of silence, which can bind a family in an imitation of life, and a nation with a false sense of justice.”

Strong Island will premiere on Netflix on September 15! Thomas Allen Harris speaks with director/producer Yance Ford about his powerful family memoir.

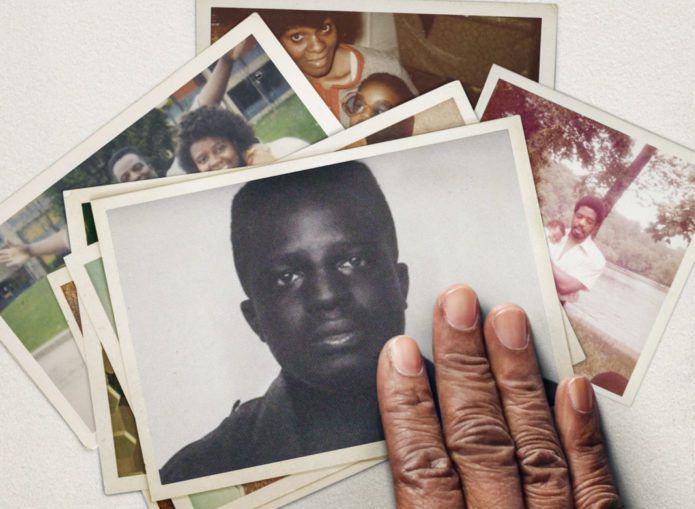

Williams Ford Jr., Lauren Yance Ford – polaroid in frame still

Thomas Allen Harris: Yance, great to be speaking with you. Could you briefly describe your new film Strong Island?

Yance Ford: Thomas, thanks for much for inviting me! The answer to why I made Strong Island is both simple and pretty complicated. First off I made the film because the silence that had closed in around my family after my brother William’s death became harder to live with than the fear of telling his story.

Secondly I made the film because unfortunately my family had been living with the consequences of my brother’s murder for 15 years. I had direct experience with what it means for the CJ system to fail to prosecute people who kill African Americans in the name of fear. It was important to share the story of family because it helps understand the past but also is a flag about the future.

The film is really carried by the strength of its characters. I think that William feels so intimately connected with so many people because the film invites you into our family from its inception, not from the murder. He would have loved your work and what you do.

TAH: At the end of the film your brother feels like he’s my brother. He isn’t a victim and he certainly is no longer absent. I’d like to turn to the family photos which in someways are like a kind of character. There are lots of family photographs in your film, images of your parents from their budding romance in grade school in Charleston to becoming adults, migration to Brooklyn, establishing their careers in education & civil service to going for the American dream of home ownership in the suburbs. These images show a rich tapestry of humanity despite the tragedy. Were you always aware of these family pictures and your parents insistence of the creation of them?

YF: I knew there were great photos of my brother, sister and I growing up because they were around our house growing up. I had NO IDEA that there were photos of my parents as teenagers in Charleston and my mother had misplaced their wedding photos. It turns out that my father was the family photographer. His insistence on photographing us, in my opinion, was about creating a visual history – he didn’t have photos from when he was a child. and documenting our family was important to him.

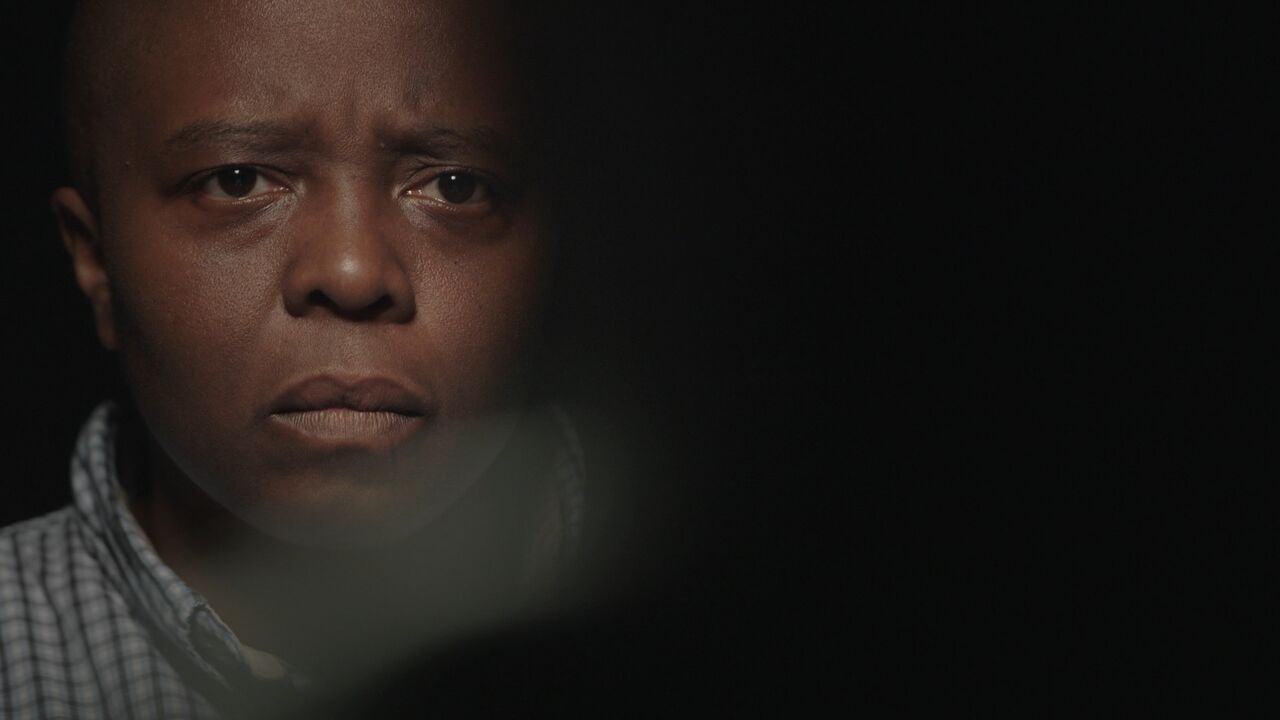

Yance Ford – frame still / Credit: Netflix

TAH: Did the process of the film force you to uncover more images that you knew of initially?

YF: Yes! There is an unexpected plot twist with one of the characters in the film. And in the aftermath of that twist the number of photographs in my possession tripled in number. We spread them out on a huge conference table and they covered the entire thing. The new discoveries actually changed the way the photos functioned in the film.

TAH: I was intrigued by the mise en scene of you engaging in your family photos that almost pulsed throughout the film – they seemed to be informed by both minimalism & performance. You are a formally trained artist, how did you decide to shoot your engagement with the photos?

YF: At first the photos were shot and presented as evidence. Into frame, pause and out of frame. At first I was using them as proof of life (in the way kidnappers have to produce a pic of someone with a current newspaper before ransom is paid).

After the plot twist (spoiler alert – it was my mother dying) it was hard to use the photos solely in that way. My producer Joslyn Barnes really pushed me to treat them with care as opposed to treating them like objects. That’s when they became so charged, so alive.

TAH: So they ultimately played a role in shaping the film?

YF: Yes, the photographs in the film are invitation, history, evidence, love. The way I handle them also communicates something about my character. They are an essential part of how the movie was conceived even though the execution changed with time.

We are lucky to have them.

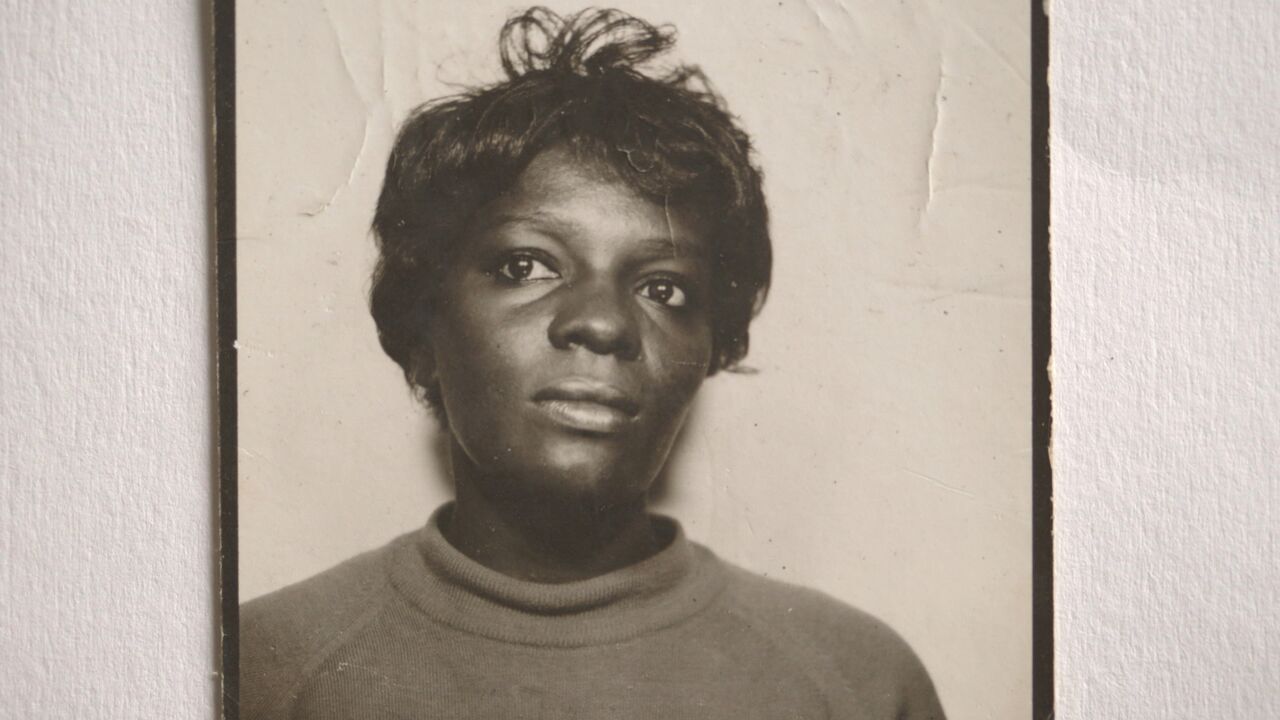

Barbara Dunmore Ford – polaroid

TAH: I loved seeing your hands handle them. The touch became very special. So different from the experience of handling digital images.

The paper, the dates, the color – there is so much texture in these photos. When you touch them you can feel the difference in older photos and newer ones – there isn’t the type of digital sharpness that can cool emotion.

YF: My brother’s journal was a huge discovery for me. When my mother first gave them to me I dismissed them as corny love poems by my older brother that I did NOT want to read.

But when I got to Copenhagen I had them shipped to me and I read them again away from my regular life. I was able to see in his writing the same kind of documenting of personal history that my father had done through photographs.

William refers to members of my family throughout his journals and in letters from him that I have as well. He did not have the capability to create photographs but his language is visual.

TAH: Visibly you change in the course of the photographs and home movies – young to adult, also in terms of gender — How did you change over the course of the film?

YF: That’s a big question because so much changed over those ten years.

TAH: I hear you!

YF: I tell people that the simplest way to understand my gender is to look at me.

You know how much it takes! Out of you and from you and you know how much it gives as well.

This film gave me the gift of authenticity. I had known – since the day I was born IMHO – that I did not conform to my gender. And the film created the space for me to be honest about that in the way that public and private lives don’t always contain the same info.

TAH: This is such a timely film – connecting us so much with Black Lives Matter and the killings that gave rise to this movement. You deal head on with the contradictory situation of being both Black and a citizen in this country. What do you hope young people will take from this film?

YF: I hope people understand that Black Lives Matter- they mattered in 1944, in 1992 and in the years since then.

I hope people begin to see the trajectory of violence over time and start to accept it- rather than deny what is obvious.

Of course we now have studies and scholarship to support the lived experience of black people in America but I hope Strong Island moves us toward believing people about their own experiences.

TAH: Shooting your mom – I was repeatedly struck by her beauty (both in term of her physical appearance – a grand dame but also in your regard of her and her inner light.)

YF: Yes. The crazy thing is that she was like that all the time.

TAH: The tableau you created called to mind the work of Mickalene Thomas and my own celebration of my mom in my work and that in my brother Lyle Ashton Harris.

YF: Black mother’s have a certain light – both for themselves and for their families. And that light is something that lives in their children and that for you and I draw our curiosity as artists.

TAH: How do you expect this project to change the direction of your work?

YF: Strong Island has helped me believe that audiences will go wherever you take them.

A formally shot film about a murder and a family coming apart could have been hand held but it didn’t feel right. This film tells me that my creative instincts are true and I will let them guide me and not doubt them.

I hope to continue to create work about black people contemporary black life both now and set in the future.

TAH: Thank you Yance for sharing your thoughts and for making this blessing of a film!

YF: Thank you Thomas – it’s such an honor to chat with you and to be in touch with the Family Pictures USA audience! I’m thrilled to share Strong Island and so happy you liked the film.

Keep taking pictures!

Yance Ford, who is transgender, is a recipient of the Creative Capital Award, a MacDowell Colony Fellowship, a Sundance Documentary Film Program Fellowship, and was among Filmmaker Magazine’s 25 New Faces of Independent Film in 2011. For ten years Ford was privileged to work as Series Producer for the PBS showcase POV and where his curatorial work helped garner more than 16 Emmy nominations. Ford is also an architectural welder, and while at Modern Art Foundry he helped assemble the sculpture “Maman” by Louise Bourgeois—the series of three spiders exhibited at Rockefeller Center, and now on permanent display at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain.

What was the purpose of Kevin telling about the limousine that showed up after the murder? It was never mentioned again in the film

Hi Kathryn,

The limousine is symbolic of the extra-judicial influence over law enforcement in Suffolk County, Long Island, NY that has been a problem for generations.

Long Island is- to this day- dealing with corruption in the DA’s Office.

The limo was there that night because it could be; because operating outside of procedure was the rule rather than the exception. And it still is.

Thanks,

Yance Ford

Director

Strong Island

Your film was beautiful. Thank you for sharing something so personal and true. Godspeed..