“In Afro-Atlantic Flight, Michelle D. Commander traces how post-civil rights Black American artists, intellectuals, and travelers envision literal and figurative flight back to Africa as a means by which to heal the dispossession caused by the slave trade. Through ethnographic, historical, literary, and filmic analyses, Commander shows the ways that cultural producers such as Octavia Butler, Thomas Allen Harris, and Saidiya Hartman engage with speculative thought about slavery, the spiritual realm, and Africa, thereby structuring the imaginary that propels future return flights. She goes on to examine Black Americans’ cultural heritage tourism in and migration to Ghana; Bahia, Brazil; and various sites of slavery in the U.S. South to interrogate the ways that a cadre of actors produces ‘Africa’ and contests master narratives. Compellingly, these material flights do not always satisfy Black Americans’ individualistic desires for homecoming and liberation, leading Commander to focus on the revolutionary possibilities inherent in psychic speculative returns and to argue for the development of a Pan-Africanist stance that works to more effectively address the contemporary resonances of slavery that exist across the Afro-Atlantic.”

Thomas Allen Harris (left) and Michelle D. Commander (right)

Thomas Allen Harris: Could you talk briefly about the inspiration for Afro-Atlantic Flight and when you realized that this was indeed going to be a book?

Michelle Commander: The idea for Afro-Atlantic Flight began way back in 2005, when I took a month-long trip to Ghana with one of my best friends from graduate school. Inspired by a course that I had just completed at the University of Southern California, I traveled to Accra with a project in mind about transnational feminism, and I spent a couple of weeks speaking with the directors of various women’s organizations on the wonderful work that they were doing. At the same time: it was my first visit to the African continent, and I was falling in love with Ghana. I began interrogating the connection that I was feeling to the place (and this was before we even toured the slave castles in the Central Region), particularly because I was meeting African American expatriates at nearly every turn and I assumed that they must have had similar affective responses to what I was experiencing.

My dissertation ended up being about African American travel narratives and engaged in a comparative analysis of African American expatriation to Bahia, Brazil, and Ghana through the lens of Pan-Africanism. Once I committed to the general of idea of tracing how people transitioned from cultural roots tourist to expatriate, I knew that it was going to be a book eventually. Though, looking back, I had no idea what that actually entailed. When I hold my breath and venture to look at my dissertation, I realize that it was a necessary exercise that I undertook in tracing the narrative arc because I was able to locate the common threads in the travelers’ politics as well as in their articulated desires for liberation, which compelled them to move.

In Afro-Atlantic Flight, I argue that since the Middle Passage, African Americans have perpetually migrated on local and global scales to escape social alienation, dispossession, and certain death. Grounded in ethnographic, historical, literary, and filmic analyses, my book is a study of African American cultural producers, travelers, and historical preservationists who elect to journey toward imagined Africas in the post-1965 moment to satiate their longings for freedom and origins through their works as well as in their roots tourism in and actual permanent migrations throughout the Afro-Atlantic, particularly in Ghana, northeast Brazil, and the U.S. South.

TAH: My film, É Minha Cara/That’s My Face (2001) and Saidiya Hartman’s book Lose Your Mother both deal with diasporic journeys. In the construction of their narratives as spiritual journeys, both texts move beyond the binary of race. How do you see these treaties on diaspora as different from the focus of previous works in diaspora studies? And what kind of intervention do you see your book making?

MC: Both works demonstrate the ends of diaspora; that is, they show what diaspora – the forced dispersal of a group from their homeland – wrought on the one hand. On the other hand, they give voice to what the processes of recovery, using the political and creative imaginations, and exerting the will to live might look like as radical reactions to continued oppression in post-transatlantic slavery societies.

MC: Both works demonstrate the ends of diaspora; that is, they show what diaspora – the forced dispersal of a group from their homeland – wrought on the one hand. On the other hand, they give voice to what the processes of recovery, using the political and creative imaginations, and exerting the will to live might look like as radical reactions to continued oppression in post-transatlantic slavery societies.

As far as other travel narratives relating to the African diasporic experience, I find that É Minha Cara (2001) and Lose Your Mother are similar to texts such as Eddy Harris’s Native Stranger in that they speak of a curiosity that many African diasporans have about their ancestors and ancestral homelands. In Eddy Harris’s narrative, however, there is a way in which misrecognitions, differences, and the breach are emphasized as the main themes in the historic relationship between Africans who live on the continent proper and diasporans. I find that you and Hartman gesture more definitively toward the importance of imagining possibilities for recovering lost histories as well as learning how African diasporans might radically comport themselves in oppressive societies.

Interestingly enough, É Minha Cara (2001) and Lose Your Mother both end with recognition—one that reads as sincere in your case with the young boy who sees an uncanny resemblance between himself and you. In Lose Your Mother, Hartman offers a critical reading of the cultural roots tourism industry in Ghana, laments the dearth of records about slavery, and considers the absence of evidence of our enslaved ancestors who passed through the dungeons at Elmina and Cape Coast. She elects to conclude the text by marveling at a group of young children who, she is told, is singing about the breach created by the slavetrade. Though Hartman no doubt understands the role that performance plays in such kinship displays, the very fact that their song (or at least the translator’s interpretation of it for Hartman) legitimizes her presence is heartening and she stands in that moment.

One of the major interventions that Afro-Atlantic Flight makes is its advancement of an argument for the continued necessity of a speculative posture. U.S.-based African diasporans, much like their counterparts across the globe, have endeavored to make lives despite the threat of violence and/or persistent and pernicious way in which racism and intersecting forms of oppression are renovated. I offer significant reflections on Black American “flight” concerning the location of Africa, the possibilities for diasporan return, and the significance of refiguring and democratizing master narratives about slavery. My description of the function of speculation, then, is not just that it is a liberating modality through which an individual can truly live otherwise, but also that it can be taken up as a radical tool of analysis to properly address the contemporary resonances of slavery that exist across the Afro-Atlantic.

TAH: Afro-Atlantic Flight is one of the first times that my work has been written about in the context of speculative/fantastic storytelling. Yet, that has been a huge influence of my work from the very beginning of my filmmaking 25 years ago; my work has been informed by mythology, dreams, and ideas around transformation. So it was a real honor to have the work placed in conversation with one of my heroines, Octavia Butler. Could you speak about the connection between the spiritual, psychic, and the speculative?

MC: É Minha Cara (2001) helped me sort through my interviews from Bahia, and I cannot thank you enough for that. For many days after I re-watch the film, your friend Alisa’s voice singing “go to Brazil…find the orixas there” remains in my head. And now that I’ve brought it up, it’s back again (laughs). Seriously, as a diasporan negotiating this world and its hostility toward Black people and blackness, the refrain is a reminder to center myself and continuously strive to live speculatively.

Your journey in Bahia was so fascinating to me because of the generational dreaming about Africa that anticipated your travel. Your grandfather and your mother had the desire to connect with Africa in some way and your mother realized her dream of traveling to the continent when she moved with you and your brother to Tanzania for two years. In the film, you discuss how that time away prompted you to reflect on your identity and whether you were an “American African.” I don’t want to ruin the film for those who have yet to see it, but I will say that it solidified for me the role that myths and narratives in which enslaved Africans and their descendants triumphed over their oppressors play in where and how African Americans travel. For instance, Candomblé, a syncretic faith that enslaved West Africans in Brazil crafted by pairing figures in their traditional pantheons with Catholic saints, allowing them to retain subversively their traditional African belief systems, inspires African American cultural roots tourists spiritually and politically and is listed consistently by my interviewees as the major element of Bahian society that compelled them to expatriate.

Lunch hosted by University of Tennessee Knoxville’s Africana Studies department, with Thomas Allen Harris, Michelle Commander, grad student Jessica Gatlin and Dr. Althea Murphy-Price.

TAH: Unlike in Europe and Africa, the United States does not possess as strong a tradition of scholarship around hybrid cinematic practice – particularly around the work of people of color. Often, my work is written about in the context of documentary, which of course, my films play with (and get distributed and marketed as such.) Sometimes, my work is discussed as experimental which I also embrace. However, I’ve long lamented that the work suffers as a result of another kind of contextualization – one that is perhaps more literary – even though I am working with literal images and sounds in addition to the written text. So I am deeply grateful for your book, which I see as both pioneering and courageous scholarship. Do you see Afro-Atlantic Flight as such and in what way? And also, what path do you see it opening for others who are following to contribute?

MC: First, thank you. “Pioneering and courageous” – wow!

For a while, it was a struggle to simultaneously think through the literature, film, interviews, ethnographic observations, the problematic issues that arose in certain “return” journeys when a handful of interviewees used neo-colonial rhetoric and shared unfortunate biases, and my personal feelings about imagined cultural loss. Thankfully, I realized that what I had identified is a massive, complicated and transnational narrative of strivings that occurred and continues to occur among formal cultural producers and everyday people alike. I was intent on figuring out a way to tease out the intricacies of this imaginary, while demonstrating how they all speak to one other. The language of speculation seemed to best encapsulate what I witnessed in fictionalized accounts about slavery and its aftermath as well as in actual travels and the re-imagining of master narratives in the U.S. South.

Without giving too much away from the book, I want to quickly gesture toward an example of this that readers should look out for: there is a moment of coalescence that occurs in my reading of Reginald McKnight’s I Get on the Bus and É Minha Cara (2001) in the first chapter that carries over into the other chapters as they relate to the figure of the tour bus.

There is still so much to analyze about the afterlife of slavery throughout the Afro-Atlantic. My hope is that Afro-Atlantic Flight will inspire scholars to remain committed to interdisciplinary scholarship that interrogates how African diasporans respond imaginatively to their dispossession.

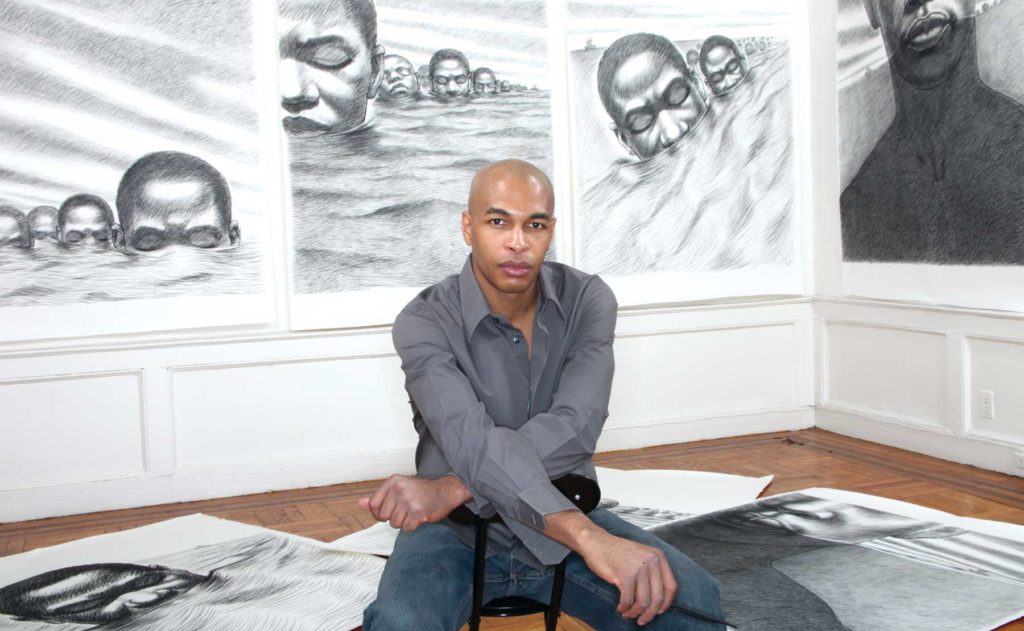

Donovan Nelson, artist for Ibo Landing 7 / Valentine Museum of Art in New York

TAH: Finally, when I look at the image on the front of the book, I am struck by events unfolding where African people are once again being transported by sea under horrific circumstances – this time to Europe & the Middle East. Does Afro-Atlantic Flight offer a critique of current events that are unfolding in our country and the world?

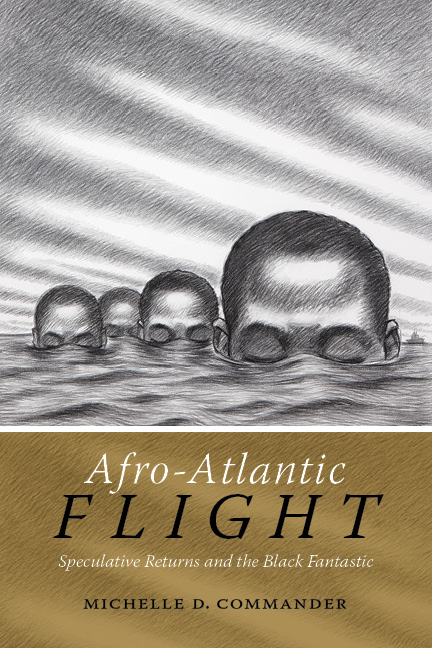

MC: Many people have commented to me about the cover – it is striking. The image, Ibo Landing 7, is from a series of sketches by a fantastic artist named Donovan Nelson (Valentine Museum of Art in New York).

One really needs to sit with that cover. It absolutely begins the story that I am telling in Afro-Atlantic Flight. The representation of possible distress – what Nelson captures and what we imagine as the audience – is moving. Questions arise about these people of African descent: Are they drowning? Is this the same person? Are they all men? What is happening? What year is it? Are they suffering? In what phase of their demise are they? Will they live? Won’t they live?

What I saw from the very moment that I came across Ibo Landing 7 is resolve. These are people who seem to be in control of their fates. The slave ship is situated in the distance behind them. They are together in the midst of a speculative act (others that occurred during the Middle Passage include mourning, suicidal flights from slave ships, refusals to eat, the revolt of enslaved people, and so on). Nelson’s entire Ibo Landing series consists of renderings of the Flying African myth, which I suggest is an origin moment of Afro-Atlantic speculation (there are numerous others). This myth is told differently across the Afro-Atlantic world, but the gist is that in rejection to their captivity, enslaved Africans radically took up “flight” back across the Atlantic with hopes of returning back to their homelands.

Diasporas can look like what I have been describing here about transatlantic slavery and they also include what you mentioned—the contemporary migration of Africans to Europe and the Middle East to escape turbulent social and political circumstances to truly have a chance at making a life. The migrants’ determination is exceedingly beautiful in the love for family, loyalty, and quest for dignity that drives them to take the risk. These journeys, though, are heartbreaking as well because of the sheer anguish and desperation that it must require to board what often are precariously overloaded watercrafts en-route to nations that are not always welcoming of those seeking refuge. That mass death is so common in such passages reminds us of the devastating ways that the past and present are connected.

What Afro-Atlantic Flight ultimately seeks to highlight and even celebrate is the historical steadfastness of a group of African descended people to respond directly to the global threat under which they continue to grapple whether under post-slavery, postcoloniality, or as residents of nations in which they are deemed and treated as the abject other.

Michelle D. Commander, Ph.D.

Michelle D. Commander was born and raised in the midlands of South Carolina. Currently, she is an associate professor of English and Africana Studies at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Commander received her Ph.D. in American Studies and Ethnicity from the University of Southern California in 2010. She spent the 2012-2013 school year in Accra, Ghana, as a Fulbright Lecturer/Researcher, where I taught at the University of Ghana-Legon and completed follow-up research for her first book Afro-Atlantic Flight: Speculative Returns and the Black Fantastic (Duke University Press).

Commander is also working on a book manuscript on the function of speculative ideologies and science in contemporary African American cultural production; a book-length project on Black counter-narratives of the U.S. South; and a creative nonfiction volume on African American mobility. She has also recently begun engaging in essay writing for public audiences some of which can be found on her website.

Learn more about Michelle Commander and her work here. Her book, Afro-Atlantic Flight: Speculative Returns and the Black Fantastic, can be found on Amazon.

Beautiful. Thank you for putting words to my personal and political experience, as an African Diaspora traveler, that I have had no words for– imaginings, dreams, desires, but no solid words or concepts. All of your work, Thomas, Michelle and all of the other authors, artists and thinkers sited make it possible for us and our generations to continue. I look forward to reading the book.

I apologize for the late response, Gail! Thank you for your post. I’m so happy to hear that I was able to articulate some of what you experienced during your travels. I hope you enjoy Afro-Atlantic Flight! -mdc