“For most of the seven decades during which Marjory W. Wilkins made photographs, she was best known as a documentary photographer of the Black community. Her body of work comprises in artist Carrie Mae Weems’ wonderfully evocative phrase— “a tender record.”1 Wilkins began in the now vanished inner city neighborhood where she grew up, Syracuse’s Old 15th Ward, largely demolished in the 1960s Urban Renewal. By age eight, she was looking through the viewfinder of her grandmother’s big box Brownie; by ten she had her own camera. A cascade of pictures ensued: family and friends, elegant home entertainments, reunions, groups of Black veterans and businessmen, jazz musicians who jammed with her saxophonist husband David in clubs or in the din- ing room, dance and choir performances, portraits, even a late fondness for sensual floral close-ups.

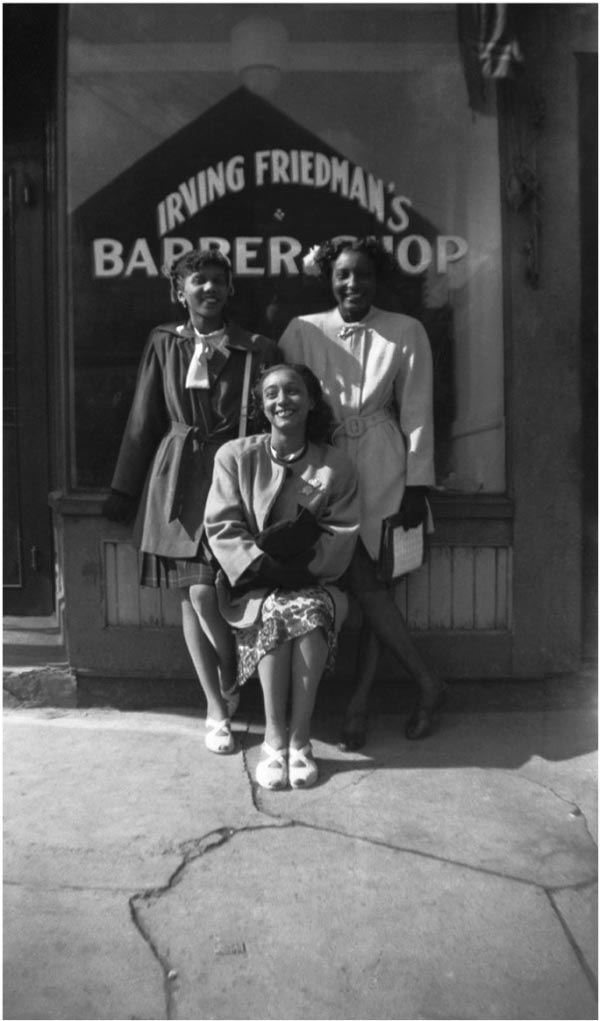

Marjory W. Wilkins—Barbershop, 1949/2008 Pigmented inkjet print, 16 x 10″

For years, Wilkins exhibited in the community, at Beauchamp and Petit branches of the county library system. In 1987 she participated in a group show at Onondaga Historical Association titled The Wilkins Family Photographically Speaking. She donated prints to OHA’s collection during the 1980s. The Paul Robeson Performing Arts Company’s archives contain pictures she took over twenty-six years. She also contrib- uted to the Beauchamp Branch Neighborhood Photo Documentation Project, begun in 1993 as part of a state-wide heritage program, which aimed to record the Black community served by Beauchamp, including the historic 15th Ward. In early 2006 the Community Folk Art Center hosted a broad retrospective of her career titled Eye Witness.

During the winter of 2005–2006, when I began working with Wilkins around her early black-and- white images, the International Center of Photography in New York City mounted the landmark exhibition, African American Vernacular Photography. Address- ing the battle for visual definition of the Black community in which such images played a pivotal role, co-curator Brian Wallis wrote in the show’s catalogue of still-prevailing notions that framed such images as unschooled, local, everyday images with “no apparent aesthetic ambition.”2 I saw this exhibition that January; those images and the catalogue’s incisive reappraisal of Black vernacular work crystallized a growing conviction that portions of Wilkins’ work could hold their own in this broader company even for viewers with no local connection.

A 2008 Light Work Grant enabled Wilkins and myself to prepare a focused selection of her early work for restoration and new digital prints. Digital Lab Manager John Wesley Mannion and his interns worked on this project at a pace that allowed the artist to participate fully in editing and printing choices. Half of the images restored were exhibited that fall; the entire group was shown in May 2010 at ArtRage Gallery and in February 2011 at Syracuse Stage Coyne Gallery as the exhibition A Tender Record.

The Light Work project marked a turning point in our appraisal of Wilkins’ work too. What do we “see” when we look at vernacular and historic photos, and what do we mean by “artist”? She has been called a “naïve” photographer—her first formal training was a course in wet developing at Community Darkrooms when her son David was a photojournalism student at the Newhouse School but Wilkins was born into a community of picture takers that initiates and apprentices its youngsters with role models and mentors, abundant examples, early exposure to practice, and a fluent grasp of composition. Her description of how she taught her own six children to take pictures echoes the vocabulary of John Sarkowski’s assertion that framing is “the central act of photography”3 and that of Robert Adams regarding the “revelation of shapes” and their relation to one another composition that framing creates.

Certainly many artists recognized her as one of their own, even though Wilkins said many times that she was not an artist. Perhaps her relationship to that term was more complicated than meets the eye. What she did not want was the battle for critical approval, the scramble for status and money, the separation from her own community that mainstream notions of artistic success sometimes entail. Instead she directed us to an older vision of the artist’s place and the artist’s job, to the tradition of art-as-gift.”

Nancy Keefe Rhodes

1. Recorded interview, September 24, 2008.

2. Brian Wallis, in African American Vernacular Photography, eds. Brian Wallis & Deborah

Willis. (International Center of Photography/Steidl, New York, NY, 2005), 9.

3. John Sarkowski, The Photographer’s Eye. (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, 2007), 9.

4. Robert Adams, Beauty in Photography. (Aperture Foundation, New York, NY, 1996), 68.

The image Barbershop was featured on the cover of the catalogue for the exhibition Marjory W. Wilkins: Early Black & White Photographs, curated by Nancy Keefe Rhodes

as part of her Light Work Grant exhibition in 2008. Copyrighted images used with permission.

Nancy Keefe Rhodes writes about film, photography, and visual arts. She is the editor of Moving Images for Stone Canoe Journal.

This looks wonderful & I’m very glad to see it’s up. Please note that it’s reprinted from the Light Work Annual (2012), with their permission.

The woman sitting down is my mother Gloria Rohadfox Wilson.

Hi Timothy, the team would love to know more about this photograph of your mother. Would you mind sharing your story with us. I’m happy to be in touch via email to learn more.

Aryana, Digital Producer, Family Pictures USA